“Balance is not just one sense, but a complex puzzle comprised of many interlocking pieces, including stability, strength, range of motion, the ability to anticipate and react.”

A research collaboration between Deer Lodge Centre and the University of Manitoba aims to give therapists better tools for assessing falls risk

By Ryan McBride

Not falling over is harder than you think. Or at least it’s more complicated: the interactions of brain, muscle and sensation that go into keeping us upright under even the best of circumstances are subtle and varied. The ability to maintain balance is like a delicate gyroscope wired into our senses, our muscles, and our ability to react to anything that might throw us off: the edge of a carpet, a patch of uneven ground, or ill-fitting footwear.

Under less ideal circumstances, or when there are impairments in the body’s systems that maintainbalance, staying upright proves to be a challenge many people know all too well.

One of the most dangerous consequences of compromised balance is a bad fall, which can lead to serious and sometimes life-threatening injuries. Bad falls are also an all-too-common reason for admission among the many clients requiring care from Deer Lodge Centre’s geriatric rehabilitation program—so when a researcher from the University of Manitoba approached the Centre about exploring a new test that might help physiotherapists better assess their clients’ risk of falling, the answer was a hard yes.

“A complex puzzle”

Kathryn Sibley is an assistant professor in the U of M’s department of Community Health Sciences and a scientist in the Knowledge Translation Platform at the Centre for Healthcare Innovation. She’s interested in why people fall, and in testing tools clinicians can use to assess and treat fall patients.

“Balance is not just one sense, but a complex puzzle comprised of many interlocking pieces, including stability, strength, range of motion, the ability to anticipate and react,” she says. “Even simply identifying the pieces themselves is the subject of a great deal of research going on right now. We keep discovering new pieces. Then we have to figure out how they interlock with the other pieces we know keep us standing upright.”

Several years ago, another group of balance researchers developed a comprehensive test to measure the performance of each puzzle piece in people of all ages and backgrounds. A more concise and user-friendly version of the test, designed for clinicians to use on the job, came soon after. It’s this version—the Mini BESTest—that Deer Lodge clients and clinicians will work with Sibley to assess.

In January, Sibley and her team will begin training physiotherapists at Deer Lodge Centre to conduct the project, which is funded in part by a substantial grant from the Deer Lodge Centre Foundation. Over the next eight months, they will perform the Mini BESTest on approximately 65 patients and residents on the Centre’s geriatric rehabilitation units—older adults who are recovering from illness, injury or age-related frailty, and who display evidence of balance impairment. Participants will be assessed on their ability to complete 14 activities, including stepping over obstacles, standing on one leg, and turning while walking.

“A tool that works”

Cara Windle, Deer Lodge’s Clinical Service Leader for Physiotherapy, says she and her colleagues are excited about the project because there’s a definite need in their profession for more meaningful and thorough balance assessment tools.

“Many of our clients are functioning at a very low level,” she explains. “It’s very challenging to find a tool that works for those folks, rather than something aimed specifically at people who are well enough, for instance, to still live on their own in the community.”

While Sibley believes the Mini BESTest, or aspects of it, may provide the right solution, the test hasn’t been studied on geriatric rehabilitation patients.

Each participant will be tested twice. “Obviously the first thing we want to know is how valid and reliable the test is for geriatric rehab patients. Can they even use this test? How many of the activities it measures are they able to perform?”

Testing twice will help researchers establish what scores constitute a meaningful improvement.

Sibley and her partners will also compare the scores to those from other tests commonly employed. Establishing this basis for comparison is key, Sibley says, because it places the project’s results into a useful context for other researchers around the world.

Ultimately, she says, “The data we collect will help Deer Lodge and other facilities like it serve their patients better, and make more informed decisions about how they might adopt the test.”

“Close to the edge”

Physiotherapists treating balance problems face a common conundrum: How do you challenge a patient’s balance to accurately assess the limits of their abilities, while managing their safety?

Susan Bowman, Manager of Physiotherapy at Deer Lodge, and one of the project’s facilitators, says that in some cases, “therapists struggle to find ways to challenge patients and take them close to the edge of maintaining their balance because of the risks of causing a fall. On the other hand, we need to get closer to that edge for a more accurate assessment.”

Sibley says the Mini BESTest may offer a solution through how it assesses reactive balance, a skill that helps us recover when our balance is challenged. “When you or I trip on a rug, we have this rapid muscle response that helps us recover. It feels automatic. But someone older or with compromised balance may not have that same response. This test has a very specific procedure to challenge the limits of a client’s balance by triggering that reaction while using strategies to keep them safe and secure.”

This is important to clinicians such as Windle. She’s concerned that test results, usually conducted in a controlled in-patient setting, don’t always indicate how patients will cope with the less predictable environment they encounter at home. “That lack of reactive balance is often what leads to falls that bring people here, or brings them back here,” she says.

Windle, Sibley and their collaborators hope that the Mini BESTest will demonstrate enough sensitivity to measure the abilities of clients with vastly different functional abilities, from the relatively mobile to the profoundly frail. “Just because someone does very well on one test doesn’t mean they aren’t still at risk for a fall,” says Bowman. “It just means the test may not be sensitive enough to challenge them where their balance is weak.”

Windle offers an example. “Sometimes we ask a patient to do a Timed Up and Go test, where they stand from a chair, walk a certain distance, and come back to the chair. That gives us a sense of their risk for falling, and it’s very simple. But although there’s good evidence that suggests the score correlates with their risk of falls, we know the test is too simple to give us all of the information we require to make an informed recommendation about risk.”

“The best service out there”

Another benefit of the Mini BESTest is its scoring system, which provides an overall score along with scores for individual components of balance—vital information that can help clinicians zero in on specific components affecting poor balance, or identify factors beyond the scope of the test, such as impaired vision, dizziness due to low blood pressure, or other medical, environmental or cognitive issues, that may be contributing to the problem. Knowing the specific causes of an individual’s balance problem will help therapists devise more appropriate exercise programs and recommendations for additional therapeutic or coping strategies.

But patients aren’t the study’s only participants. Researchers are also keen to find out how the Mini BESTest helps the physiotherapists using it. Physiotherapists will themselves become research participants: once the trial is complete, they’ll be asked how easy the test was to complete, and how it changed their actual practice. “Even if it’s effective, if it’s too complicated to use in a hectic, fast-paced rehab ward, no one’s going to use it,” Sibley says.

Susan Bowman believes the test may offer clinicians the means of achieving an even better balance of care in their own practice: “We hope the results will tell us how we can challenge our staff, to help them continue to learn and grow and offer the best service out there.”

Recent News

Embracing Hope: The Impact of DLC’s Movement Disorder Clinic

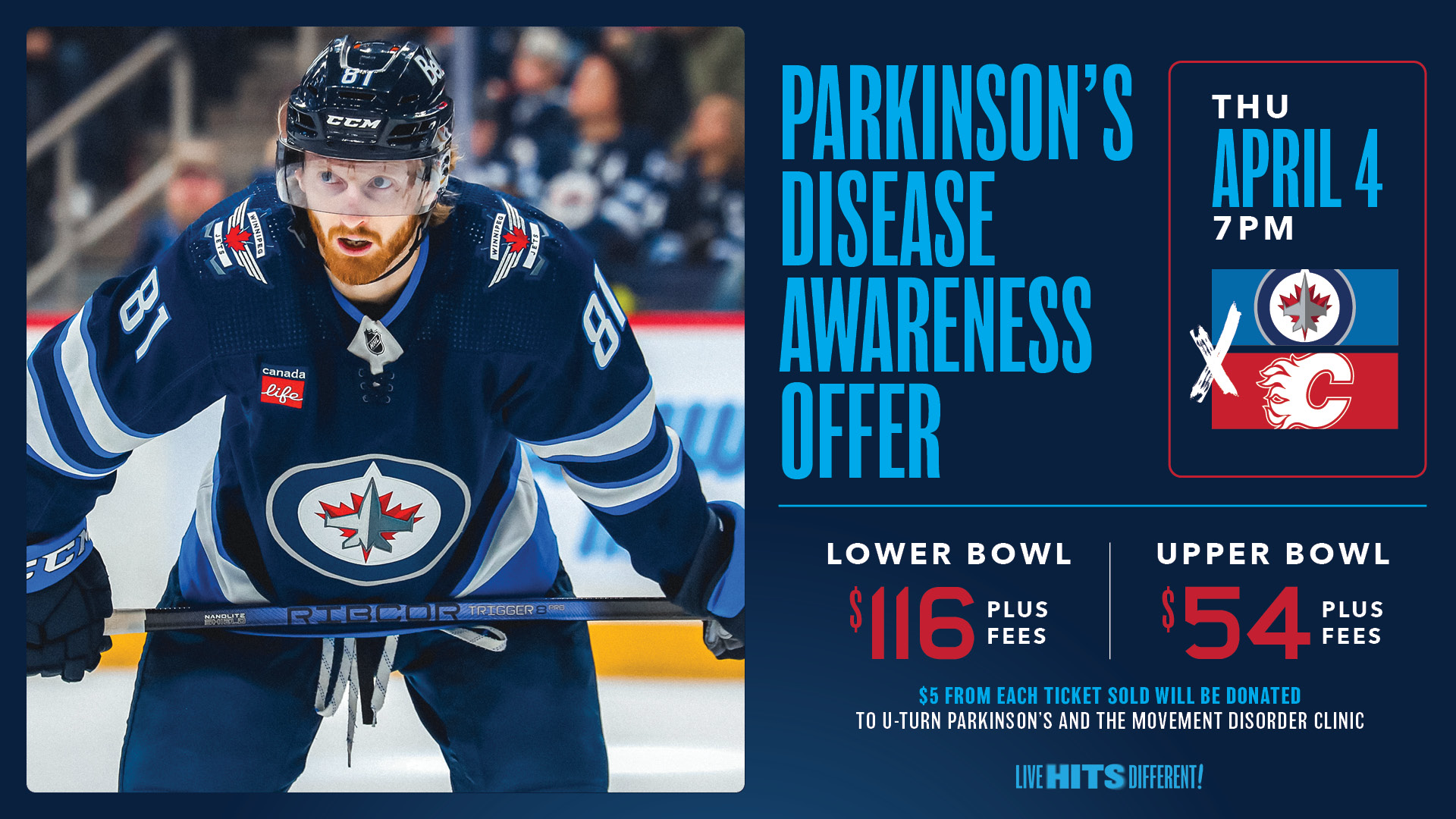

Winnipeg Jets Parkinson’s Disease Awareness Game!