The OSI Clinic at Deer Lodge Centre marches to the forefront of PTSD treatment

“Will I get better?”

It’s a question Amber Gilberto doesn’t always know how to answer for the personnel and veterans of the Canadian Forces and RCMP she treats for the impact of severe stress.

A clinical nurse specialist at Deer Lodge Centre’s Operational Stress Injury (OSI) Clinic, she says she of-ten finds herself asking, “What does better even mean? When you look at how the lives of these people will never be the same after what they endured in the line of duty, what exactly is recovery?” The OSI Clinic, which is funded by Veterans Affairs Canada, treats military and police personnel suffering from mental health conditions sustained while on duty, “whether those injuries are the result of deployment, operations, or training exercises.” Operational stress injuries include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, family dynamics issues, physical pain, sleep problems, nightmare disorder, and anxiety. The clinic treated more than 450 people last year.

“When I started here, working mostly in intake, I knew very little about operational stress injuries,” she says. “I knew even less about the military and the RCMP.”

But she learned fast — and in the process, developed a profound appreciation for the special sacrifices made by her clients.

“It’s heartbreaking,” she says, “to sit with someone who has gone into the military or the RCMP, someone who has made a principled commitment to risking their life in order to make the world a safer or more just place, someone who has come away from that duty not only broken by the terrible things they’ve seen, but uncertain they’ve made any difference at all.”

As Amber learned about PTSD treatments from on-the-job training, she began to set her sights on advancing into a therapeutic role that would let her work alongside her clients beyond the intake process. However, formal training in the OSI Clinic’s gold standard treatment protocols — including prolonged exposure therapy, cognitive processing therapy, and eye movement desensitization reprocessing therapy (see below) — required something she didn’t have: a master’s degree.

So when her boss asked if she’d be interested in applying to the Masters in Psychiatric Nursing program at Brandon University, “the timing was perfect.”

Amber focused her masters clinical work on trauma-focused treatment training, then completed her practicum at the OSI Clinic.

“The more I progressed into therapy with my clients, I noticed that trauma therapy was a big part of getting well, but sometimes a client would come to me and say, ‘I just discovered something else that helps!’ For example, maybe they’d started painting again after 20 years, and it was helping them stay in the present moment instead of dwelling on a traumatic event. I began to see these things in their lives that weren’t part of the therapeutic protocol we were following, but were just as important to the recovery process. I wanted to examine these outside elements in a way others could tap into and make use of.”

Which led to the final step in her graduate degree: a research thesis analyzing the lived experience of recovery for veterans of the Canadian Forces.

“Studying lived experience is an approach to research that says your personal knowledge of your own experience is as important as academic or professional knowledge about your experience,” explains Amber.

“My research begins with the belief that the true experts in recovery are the people living it. They inform what we need to do to help them now and in the future.”

Her research involved face-to-face, semi-structured interviews with three Canadian Forces Veterans who had each completed PTSD treatment at the OSI Clinic. Amber recorded the interviews and transcribed them, then set about scouring their content for prevailing themes.

She deliberately chose to conduct qualitative research in order to balance out and complement the vast weight of quantitative research — numbers and statistics — already informing therapeutic practice at the OSI Clinic. Amber says her research identified three major themes that contribute to the recovery journey.

First, culture plays a critical role in recovery – not only military culture, but family culture and the sub-culture of veterans living with PTSD.

“Military culture really is a separate culture distinct from our own, and that can make it difficult to integrate back into the civilian world, even when you don’t add recovery from a traumatic event to the equation,” she says. “Something utterly unique becomes deeply ingrained in you when you become part of those kinds of organizations. When you leave, you’re walking away from your identity.”

Second, relationships are a key, complex part of the recovery journey — especially relationships within the Canadian Forces.

“There’s camaraderie between members of the military quite different from any other kind of relationship, and this needs to be accounted for in the recovery journey.” And third, recovery is a journey. “Only part of the journey is the trauma-focused treatment we provide.”

Amber says the OSI Clinic has already adapted its programming to ongoing support to clients, including support groups and adjunctive programs that support all three themes in the recovery journey.

It’s important, says Amber, for those suffering from trauma to see they’re not alone in their experience — a perspective the treatment itself might not be able to provide.

“Here, they become part of a therapeutic community, one where they don’t feel they are being judged or misunderstood. They accept that they’re on a journey, and they’re not on it alone.”

Amber’s research has validated the need for these programs – but the benefits have taken even her and her fellow therapists by surprise.

“There was evidence the groups would help, and we discovered that people were indeed getting better faster, or progressing in their recovery in ways they hadn’t during formal therapy. The groups also helped the clinic see more people faster and reduced our waiting list.”

In the future, Amber plans to expand her study to include the lived experiences of veterans of the RCMP. In the meanwhile, her research has had a profound impact on her own psychiatric nursing practice.

When a patient asks her “Will I get better?”, Amber says she’s more hopeful now than when she began.

“For people who have seen the worst of the world, we sometimes have to be creative in how we reframe their experience to help them through it. All the time, though, I see people change. Somehow, they stumble upon what they need. It’s rewarding to be there when they discover they no longer have to live a certain way in order to cope with their PTSD, their anxiety, their depression. Their operational stress injury is something that happened to them, but it doesn’t define them. And that’s truly inspiring.”

Treating trauma at Deer Lodge

The Operational Stress Injury Clinic at Deer Lodge Centre offers three “gold standard” cognitive behavioural therapy treatment protocols that are recognized by the National Centre for PTSD:

- Prolonged Exposure Therapy

The therapist guides the client through re-experiencing the traumatic event by remembering it and actively engaging with reminders and triggers of the trauma. - Cognitive Processing Therapy

The client writes an account of their trauma and then reads it aloud to discover places where their view of themselves, others, and the world might be stuck. - Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing Therapy

The client uses bilateral eye movements to process traumatic memories and the sensations they evoke.

Recent News

Embracing Hope: The Impact of DLC’s Movement Disorder Clinic

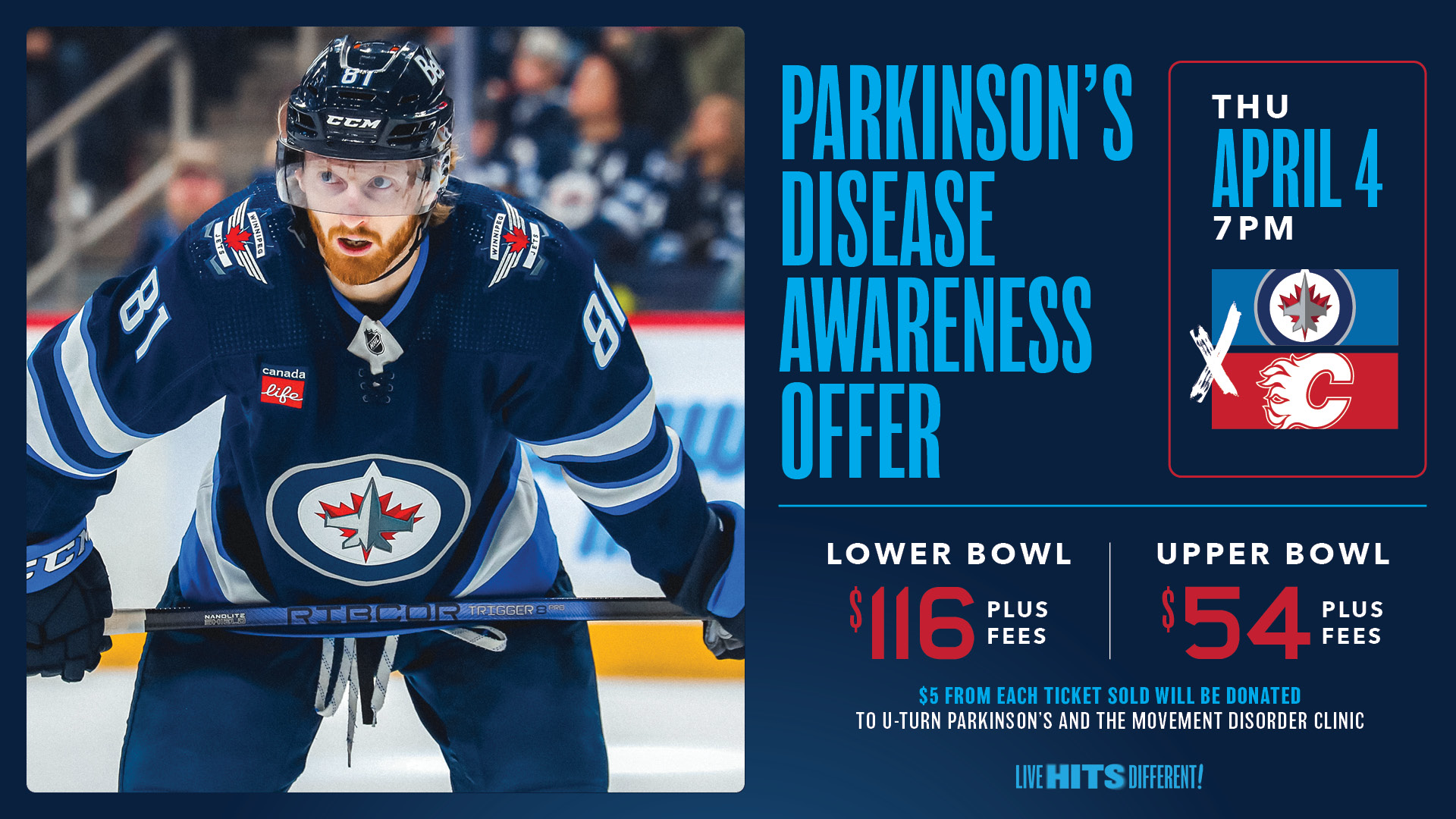

Winnipeg Jets Parkinson’s Disease Awareness Game!