The Operational Stress Injuries Clinic is helping military and law enforcement personnel and veterans escape from the grip of chronic pain

By Ryan McBride

They’re trained to put themselves in harm’s way for the sake of our safety and security. For that reason, the women and men who serve in our military and law enforcement face a unique set of occupational hazards—and many of these hazards require specialized treatment. Those who return from the frontlines suffering from acute injuries sometimes face chronic pain, an insidious condition that can wreak havoc on their lives long after the injury that caused it has healed.

Clinical psychologist Pamela Holens defines chronic pain as any pain that lingers for more than three to six months. Since 2016, she has served as clinical director at the Operational Stress Injuries (OSI) Clinic at Deer Lodge Centre, where she’s known as the go-to person for pain-related issues.

The OSI Clinic treats military and police personnel suffering from conditions sustained while on duty—chronic pain included. Holens estimates the OSI Clinic treats up to 50 chronic pain clients in a given year, a number that continues to increase, likely because more people are becoming aware of the condition and its impact on those who suffer from it. A high percentage of OSI clients end up receiving treatment for chronic pain, even if they originally came to the clinic for something else.

She cites research that says 20 to 30 per cent of the general population experience some form of chronic pain. “Among military and police organizations, that number runs closer to 50 per cent, which is not surprising, given the nature of the work they do.”

The culture of military and law enforcement organizations can sometimes make recognizing and treating chronic pain difficult, says Holens. “When you’re serving, you’re often told to suck it up, to hide any weakness and push through the pain. This can be a useful, even critical, mindset on the battlefield, or when dealing with violence. But it can also make injuries worse because they go unassessed and untreated for much longer. The pain that comes with them then becomes worse. And once that pain has become chronic, it’s a far more complex beast to deal with.”

The many dimensions of chronic pain

One reason for this complexity is the nature of pain itself. We tend to think of pain as physical. In fact, it’s much more than that.

“When you look at brain scans of people who are feeling pain, you’ll see sensory parts of the brain light up, but emotional parts of the brain also fire,” explains Holens. “In fact there are theories about how emotional issues can sometimes get in the way of treating chronic pain, because our mind is creating what we call a somatic disorder—a physical issue that may be easier for a person to cope with than the underlying emotional issue. More and more, we’re starting to look at that dimension of chronic pain.”

Once pain has become chronic, the pain itself is now the primary problem, rather than the original injury that caused it, says Holens.

Chronic pain harms its victims in a variety of ways. Holens and her colleagues evaluate these impacts using a questionnaire that measures seven functional areas, including family and home responsibilities, recreation, social activity, occupation, sexual behaviour, self care, and life support activities. “I see quite a lot of people giving me an eight or higher out of ten in three or four of those areas,” she says.

Chronic pain often affects military and law enforcement personnel differently than the general population. One reason is the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among the clients Holens treats. She says chronic pain and PTSD both operate as “overactive alarm systems in the body.” PTSD, for instance, makes victims hyper-vigilant: “You’re constantly on guard, looking for danger, even where none exists. Loud noises make you jump. A lot of my clients might have a hard time visiting a shopping mall, for example, because there are too many people around, too many unknowns. You never know what might pose a threat.”

In much the same way, chronic pain can overwhelm you with a strong pain signal from a weak trigger. “Some people liken it to a smoke detector that goes off whenever you make toast, rather than when there’s actual fire.”

With that pain comes a natural tendency for sufferers to withdraw from the activities that trigger it. Thus begins a vicious cycle: less activity leads to muscle atrophy, which leads to more pain.

Treating chronic pain

One of the first steps in treating chronic pain is to make clients aware of this vicious cycle. Next comes helping them understand that feeling pain is not itself making the condition worse. In fact, says Holens, “you need to push a little into the pain to actually move forward.”

The OSI Clinic’s introductory pain management program helps clients through this process by guiding participants through a course in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT).

“One of the foundations of ACT is values. We want you to really think about what’s important to you in your life, and ask yourself if you’re living consistently with those values. Often with chronic pain, a lot of things we value go out the window. For example, you value relationships and socializing, but you stop going out with family and friends because it hurts.”

ACT challenges clients to accept that they’ll feel pain whether they go out or stay home. “And from there, we can help them see that maybe they’d do better if they went out, because socializing with people they care about will provide meaning and purpose that has been lacking since they put their lives on hold waiting for the pain to go away.”

Holens and her colleagues ask clients to look at 10 different areas of their lives—including family, friendships, work, spirituality, and health—to explore new ways they can recommit to cherished activities. “If you’re into sports, that could mean cheering your kids on instead of playing yourself, or trying low-impact forms of exercise.”

Participants in the introductory pain management program meet with Holens every two weeks for group sessions where she offers pain management education. These meetings also give clients the opportunity to compare experiences and share progress. An online program allows clients to follow from home if their pain gets in the way of attending meetings.

The OSI Clinic’s advanced program builds on these techniques while introducing new ways clients can release their lives from the grip of chronic pain. A physiotherapist works with each client to plan a personalized pain management program.

There’s also a movement and meditation program, which operates on a weekly drop-in basis for OSI Clinic clients. Holens started the program after encountering research outlining the impressive benefits of meditation, mindfulness and yoga for people dealing with chronic pain. People who practice yoga and meditation have a higher pain threshold than those who don’t, the research suggests.

In case you’re wondering if yoga holds any appeal to the military and law enforcement crowd, the answer, says Holens, in an emphatic yes: “They know the benefits quite well. The Warrior Pose, for example, holds obvious appeal, and helps them work on strength and balance.”

Beyond chronic pain

Holens says the programs’ greatest measure of success is the number of clients who learn to live a full life with their pain, instead of fighting it. “The fact is, once pain has become chronic, a cure is unlikely. It can decrease over time, and for some the pain may even go away eventually, but the process is a long one.”

In the future, Holens hopes to develop another program for clients who want to tackle the emotional side of chronic pain.

“It’s a hard thing to ask people to confront that there might be something emotional there, keeping you locked into your pain. We’re not saying it’s all in your head (although on one level we recognize that pain literally is all in your head, because the brain generates the pain signal based on multiple inputs). We’re not saying you’re making it up, or that the pain isn’t real. It is very real. But it might be tied up in all kinds of things not directly related to your injury. That’s what we want to deal with next.”

Recent News

Embracing Hope: The Impact of DLC’s Movement Disorder Clinic

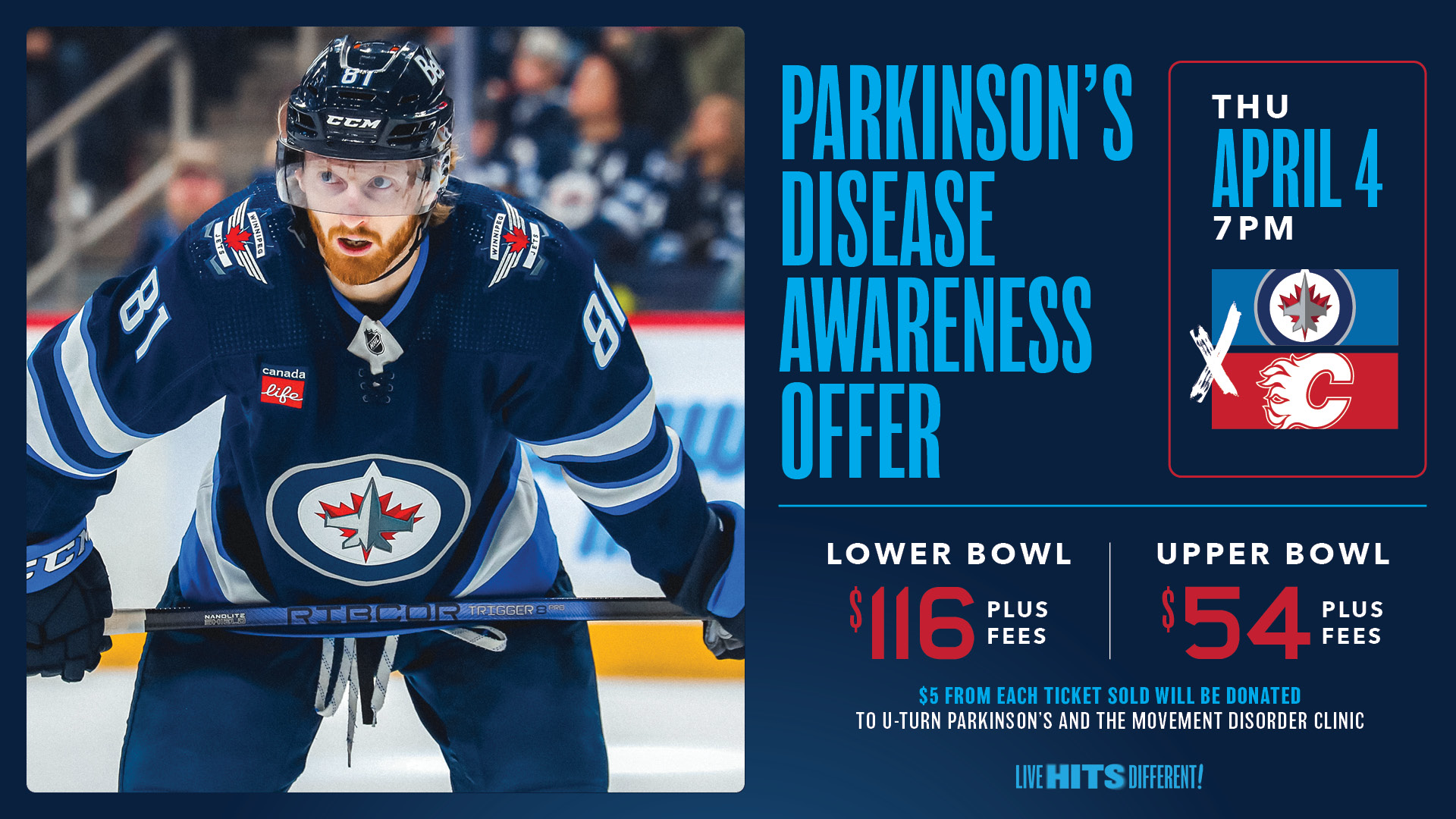

Winnipeg Jets Parkinson’s Disease Awareness Game!