Operational Stress Injuries Clinic takes complex, layered approach to treating sleep disorders among military, RCMP personnel and veterans

By Gregory Holmes

You have a forty per cent chance of encountering a sleep problem in your lifetime, says the latest research—whether it’s difficulty falling or staying asleep, or a medical condition such as sleep apnea or restless legs syndrome. If that news isn’t startling enough, the consequences of getting less than the recommended seven hours of shut-eye per night can be dire, including not only lost productivity but serious physical and mental health problems. Lack of sleep and drowsiness are also a proven major cause of motor vehicle accidents. (And worse: the Exxon Valdez oil tanker disaster was famously the result, in part, of a sleep-deprived ship’s captain.)

For Canadian military and RCMP personnel and veterans, the likelihood of suffering from a chronic sleep disturbance is even greater than it is for the rest of us. The reason, not surprisingly, has to do with the downright knotty links between sleep disorders and the mental health conditions many military and law enforcement personnel suffer from due to the stressful nature of their occupation.

In fact, for many such cases, the sleep disorder itself can become as big a problem as the condition that created it, says Dr. Murray Enns, a psychiatrist at Deer Lodge Centre’s Operational Stress Injuries (OSI) Clinic.

“Things the general public doesn’t get to see”

The OSI Clinic, which is funded by Veterans Affairs Canada, treats military and police personnel suffering from mental health conditions sustained while on duty, whether those injuries are the result of deployment, operations, or training exercises. Operational stress injuries include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, family dynamics issues, physical pain, depression and anxiety. The clinic treated more than 450 people last year.

“The OSI Clinic treats people who will predictably and repeatedly be exposed to things the general public doesn’t get to see. We may know about war or violence or crime, but experiencing such traumas with your feet on the ground is another thing entirely. Especially when your job requires you to ignore your natural human response, and approach, rather than flee from, a terrifying experience,” explains Enns.

Call it an occupational hazard. “If you lift heavy boxes all day, you’re likely to encounter back problems. If you’re exposed repeatedly to violence and death, the consequences of war or criminal activity, you’re more likely to develop a mental health condition. Not everyone does—in fact, most don’t. The OSI Clinic is here for those that do.”

Dr. Enns has been a psychiatrist at the OSI Clinic for two years. Prior to that, he served as the head of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Manitoba for 10 years. Sleep disorders are one of his clinical and research specialties. Treating them is a responsibility he shares with other OSI clinicians.

Poor bedfellows

“When you are dealing with a clinical population with mental health concerns such as PTSD and depression, the prevalence of sleep disorders is very high compared to the genral population,” says Enns.

A large number of OSI Clinic clients seek treatment for anxiety, mood and substance abuse disorders. Each of these conditions directly causes sleep disruption. In fact, for generalized anxiety disorder, clinical depression and PTSD, sleep disturbance is a core diagnostic criterion. For that reason, step one in treating the sleep disruption is to address the condition behind it. In some cases that’s all it takes. “You’re less amped up, agitated, restless. Your sleep quality improves, as does your perception of how you’ve slept.”

That’s the simplest scenario, says Enns, but hardly the most common.

“More often, the sleep problem begins to perpetuate itself even after the cause—worry about a life problem, pain, or PTSD—has been addressed.”

How a bad problem gets worse

A process called conditioning can cause a sleep problem to perpetuate itself. Conditioning sets in when people adjust their behaviours to compensate for disturbed sleep. They take a couple drinks in the evening to relax, for example, or use more caffeine in the day to stay alert. Or they try to force themselves to sleep, lying in a state of mounting frustration and clock-watching.

“That’s when sleep itself becomes a primary problem. The bed now becomes associated with angst, so that even when they’re drowsy, the moment they crawl into bed, the mental light snaps on—they’re wide awake.”

In other cases, people with sleep disturbances repeatedly change their sleep schedule so they’re no longer following a fixed routine. We all have a circadian rhythm our brain follows for falling asleep and waking up—if we set the right conditions for it. “But if you keep changing the time you go to bed and get up, it’s like you’re constantly jumping from one time zone to another as far as your brain is concerned.”

Enns says these two problems—conditioning and a poorly regulated circadian schedule—often creep in after three to six months of sleep disruption. The most common form of treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or CBT-I. A practice supported by empirical research, CBT-I focuses on changing how we think about and respond to our sleep problems with more helpful thoughts and behaviours.

Nightmare scenarios

“In many, many cases we’re treating people who’ve been deployed to Bosnia, Croatia, Afghanistan, so they’ve had some really traumatic experiences,” says

Enns. Not surprisingly, these experiences often revisit PTSD sufferers in their dreams. “They wake up activated, in a panic.”

Sometimes the right medication can suppress distressing dreams. Other times, OSI therapists will use a technique called rescripting to gain a comprehensive picture of how the dream usually evolves, then write a new ending. Practicing and rehearsing a less distressing outcome to the dream repeatedly before going to bed has been shown to substantially reduce distressing dreams and improve quality of sleep.

Medical sleep disorders

Enns says a trio of medical sleep disorders that occur in the general population—sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, and periodic limb movement disorder—are also common among military and RCMP personnel and veterans he and his colleagues treat at the OSI Clinic.

Sleep apnea occurs when breathing is interrupted during sleep and deprives the body and brain of oxygen. Restless legs syndrome causes uncomfortable sensations in the legs, along with an irresistible urge to move them; it’s often most severe when patients are lying in bed. So, too, is periodic limb movement disorder, which causes patients to kick or jerk their limbs during sleep. Treating each of these disorders might involve medication or, in the case of sleep apnea, a CPAP machine to deliver steady, positive air pressure and maintain open airways during sleep.

Waking up to better sleep treatment

The treatment of sleep disorders has evolved a great deal in recent years, says Enns. “For instance, we now have a much greater appreciation for the importance of behavioural interventions over prescribing medications. We’ve known how cognitive behavioural therapy can help treat insomnia for some time, but it’s taken us a couple decades for routine implementation of CBT-I as a frontline treatment that should be done first.”

In general, current treatments for sleep disorders are effective for OSI Clinic clients regardless of how long ago the trauma took place. Nevertheless, research is ongoing, and sufferers of operational stress injuries may be key to improving our understanding of sleep disorders and how to treat them.

“The research community is interested in military and law enforcement personnel and veterans because the consequences of military or police trauma compared to common civilian traumas may be different; their responses to treatment aren’t always the same as those found in the general population, and we’d like to better understand those differences.”

Regardless of how our understanding changes, the approach Dr. Enns and his colleagues take to treat an individual case will always remain, like the conditions and the people they seek to heal, “complex and layered.”

Recent News

Embracing Hope: The Impact of DLC’s Movement Disorder Clinic

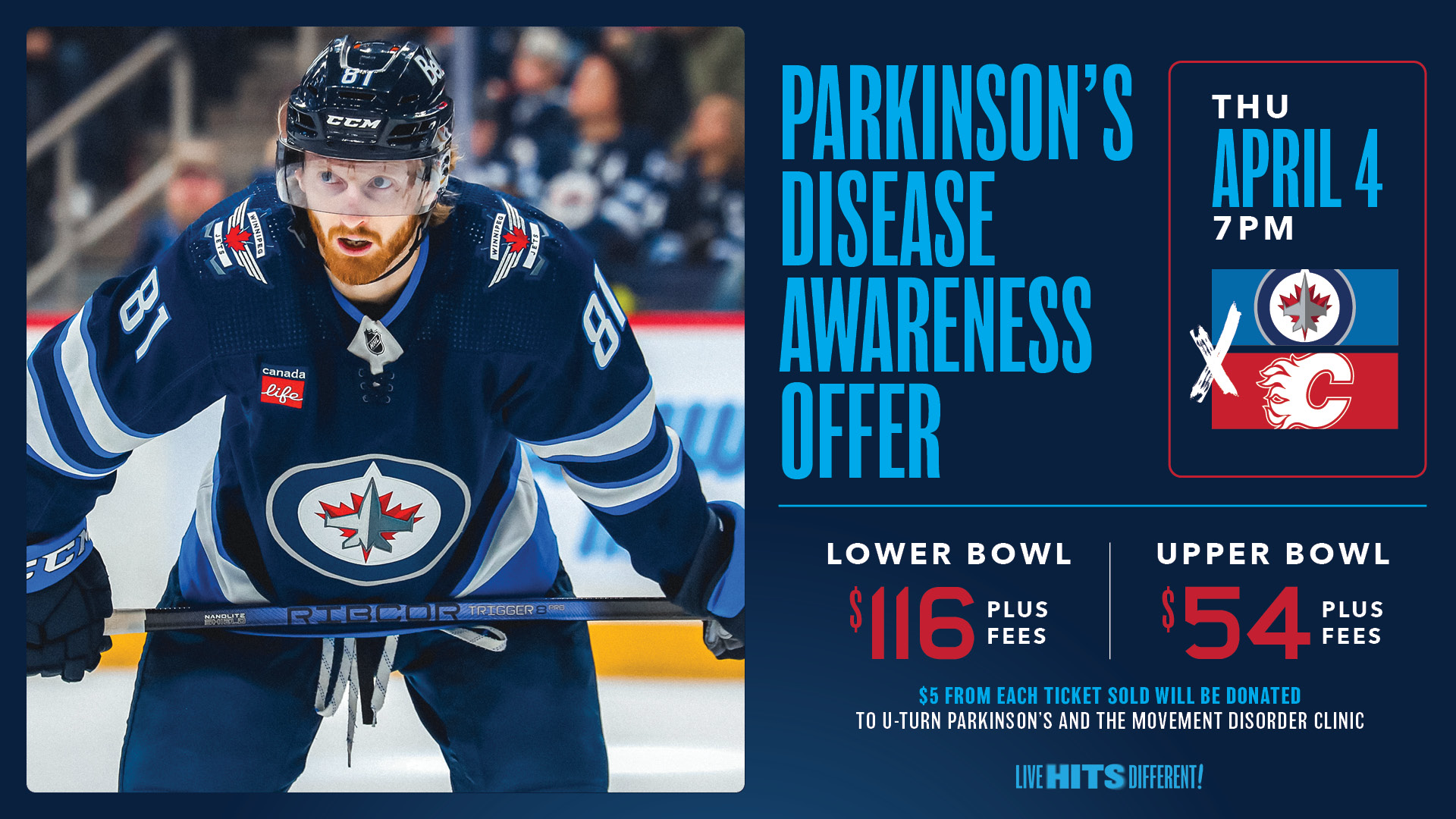

Winnipeg Jets Parkinson’s Disease Awareness Game!