By Ryan McBride

Financial abuse of the elderly in Canada is on the rise, due in part to the aging of our country’s population. Symptoms of the problem are hard to spot, and often go unnoticed and unreported, making the numbers harder to track. We do know the following sobering statistic: four to ten per cent of Manitoba seniors will likely face elder abuse of some sort in their lifetime.

One of these victims could be a friend, a family member, or you.

Abuse vs. neglect

Financial abuse of the elderly runs the gamut from stealing assets, property or money; cashing an elderly person’s cheque without their permission; forging their signature; pressuring them to change or sign a legal document they may not fully understand; or simply sharing an older person’s home without paying a fair share of the expenses when asked.

At Deer Lodge Centre, it is the social workers who are most often called upon to assess and develop a plan for addressing suspected cases of financial abuse among residents and patients, says Lisa Lloyd-Scott, the Centre’s manager of social work.

While the prevalence of financial abuse cases hasn’t grown significantly over the years she’s been a social worker, she says incidents “are not rare enough. We see cases of it more frequently than we’d like.”

Related to financial abuse is the problem of financial neglect, which occurs when family members or caregivers experience a disruption in their own lives—such as stress or the onset of dementia—and can no longer manage the finances of someone they normally support.

Lindsay Bacala, a social worker in Deer Lodge’s Dementia Care Program, sometimes detects signs that the person who holds power of attorney over a resident (often a grown son or daughter) has begun to develop signs of dementia themselves. “Suddenly they’re not paying their parent’s bills properly—not because they’re abusive, but because they’re encountering their own cognition issues.”

Lloyd-Scott estimates 10 per cent of Deer Lodge clients are impacted by financial abuse in a given year, while 15 to 20 fall victim to financial neglect.

Signs of financial abuse

Red flags that Deer Lodge staff have come to recognize include a client’s basic necessities going unmet. “We ask families to provide our residents with socks, clothes, toiletries, sometimes a small trust fund, and that doesn’t happen. Or per diem charges or utility bills aren’t being paid.”

Other signs might include a missing bank card or cheque book, or an overheard accusation of monetary theft between family members. Sometimes, what alerts Deer Lodge staff is a client suddenly not having enough funds to cover dental care, a hair cut, or favourite recreational activity.

“More than once, I’ve had a family member tell me a client of ours should have way more money in their account than they do,” adds Jamie Hall, a Deer Lodge social worker in assessment and rehabilitation. Other times, the client themselves will bring an unusual bank balance to the attention of a social worker.

Social workers must then gently peel back the layers to find out what might be behind the problem. Sometimes that means accessing bank statements to spot unusual transactions.

“We call the bank together to look over withdrawals and the client says, and that’s when we know someone else who has access to the client’s bank card of cheque book may have taken advantage of them,” says Lloyd-Scott.

Taking action

Once financial abuse or neglect are suspected, Deer Lodge’s social workers take a team approach to addressing the problem. They inform staff, the care team supporting the resident or client, and the person managing the client’s money.

“Many of our residents have trust accounts, so with the client’s permission we work with the our finance department to try to help our clients.” explains Lloyd-Scott. “Sometimes we alert family members to contact the client’s bank.”

Then the time for difficult conversations begins.

“It’s tough on families when they have to go against each other,” says Bacala. “I’ve seen some clients who are cognitively impaired but are still able to understand what’s going on. Just gathering all that information to present to them can create huge conflicts between them and other family members, not just the abuser. It’s a sad situation.”

In some cases the source of the financial abuse isn’t a family member, but a trusted friend, neighbour or community member. When this is the case, the scenario often involves social isolation, says Lloyd-Scott. “They pull the victim away from their family so they’re forced to rely on this person for everything.”

Next steps usually depend on the mental competence of the victim, says Hall. “If they’re fully competent, it’s up to them on whether to take action. If they don’t want us to get involved, or don’t want to take action, we can’t.”

It’s a different story when the victim isn’t legally competent. “If they’re vulnerable in that way, we get them assigned a public guardian and trustee. If there are loved ones we believe would act in their best interest, we encourage them to pursue committeeship so they can act on their loved one’s behalf.”

For clients willing and able to proceed, social workers might then contact Winnipeg Police Services. “The WPS is exceptional at working with individuals and their families in a way that doesn’t alienate anyone,” says Lloyd-Scott. “It’s important that the victim still has a support system around them.”

Abusers are sometimes formally charged with a crime, but Lloyd-Scott says, “That’s a horrible situation, and I’m not sure there are any winners at the end of that road.”

Either way, it’s rare that victims of financial abuse get back what was taken from them. This can have devastating consequences for the victim, regardless of the amount stolen.

“Personally, I’ve never seen a case where a victim has received even partial restitution for their loss,” says Lloyd-Scott. Some of the cases she’s witnessed have involved large amounts of money, such as insurance settlements. “Hundreds of thousands of dollars are suddenly just gone. But I’ve also seen scenarios where it’s 20 dollars here, 20 dollars there. For someone living on a fixed, limited income, that can mean the difference between getting your groceries for the week, or going hungry.”

Motives of financial abuse

“People who commit financial abuse are often in dire financial straits themselves. They might be in debt, or have other addiction issues motivating their actions,” says Lloyd-Scott. In other cases, a parent who has helped a child financially throughout their lifetime can no longer afford to when they move into long-term care, leaving the child feeling desperate.

Abuses can start out as small, seemingly justifiable actions that quickly slide down a slippery slope. “Sometimes it’s as simple as saying to yourself, ‘It’s mom, she wouldn’t mind if I just took 20 dollars for groceries. Or perhaps the abuser has cared for the victim and feels the money they are taking is their due. Or maybe they had an agreement at some point where the victim told them ‘all this will be yours’—so the abuser starts taking it all now.”

An incomplete picture

Lloyd-Scott says it’s critical for social workers helping victims of financial abuse to remember they rarely (if ever) have access to the full context, including conversations that happened behind closed doors or have since been forgotten.

“Sometimes the person committing the financial abuse feels entitled because of a lifetime of experiences they’ve had with this family member we’re now taking care of, and of which we know nothing. It’s not our place to judge that—it’s our place to find a solution that works in the best interest of everyone involved.”

In social work, the first line of focus is always the family unit, she says. When it proves impossible to accommodate everyone, she and her colleagues make the welfare of individual in their care their highest priority.

Even then, she says, not every situation is black and white.

“We have clients who know they’re being taken advantage of and choose to allow that to continue. There are circumstances behind those choices we’ll never understand. Again, we don’t judge.”

What to do if you suspect someone you know is the victim of financial abuse

Explore cautiously and ask questions gently, without accusing anyone. “Do you have all the food you need? Did so-and-so take you to the bank last week?” You don’t want to alienate the individual you’re concerned about.

If you need support and assistance, call:

- Senior’s Abuse Support Line at 1-888-896-7183

- Age and Opportunity Support Services for Older Adults at 204-956-6440

- Protection for Persons in Care at 1-866-440-6366 or 204-788-6366

If the person you’re concerned for is a patient or resident at Deer Lodge Centre, talk to one of our social workers.

And, of course, if you believe someone to be in imminent danger, call 911.

For more information, visit the Age and Opportunity Elder Abuse Prevention Services at www.ageopportunity. mb.ca/services/elder_abuse.htm

Protect yourself from elder abuse

- Stay sociable as you age and maintain and add to your network of friends and acquaintances

- Keep in contact with old friends and neighbours if you move in with a relative or move to a new address

- Develop a buddy system with a friend outside of the home. Plan for at least weekly contact and share openly with this person

- Ask friends to visit you often—even brief visits allow for observations of your well being.

- Participate in community activities

- Have your own telephone, and post and open your own mail

- Arrange to have your pension cheques or other income deposited directly into your bank account

- Get legal advice about arrangements you can make now for possible future disability, such as powers of attorney

- Keep accurate records, accounts and lists of property/assets available for examination by someone you trust, as well as by the person you or the court have designated to manage your affairs

- Review your will periodically and do not make changes to it without careful consideration and/or discussion with a trusted family member or friend

Source: www.winnipeg.ca/police/TakeAction/elder_abuse.stm

Recent News

Embracing Hope: The Impact of DLC’s Movement Disorder Clinic

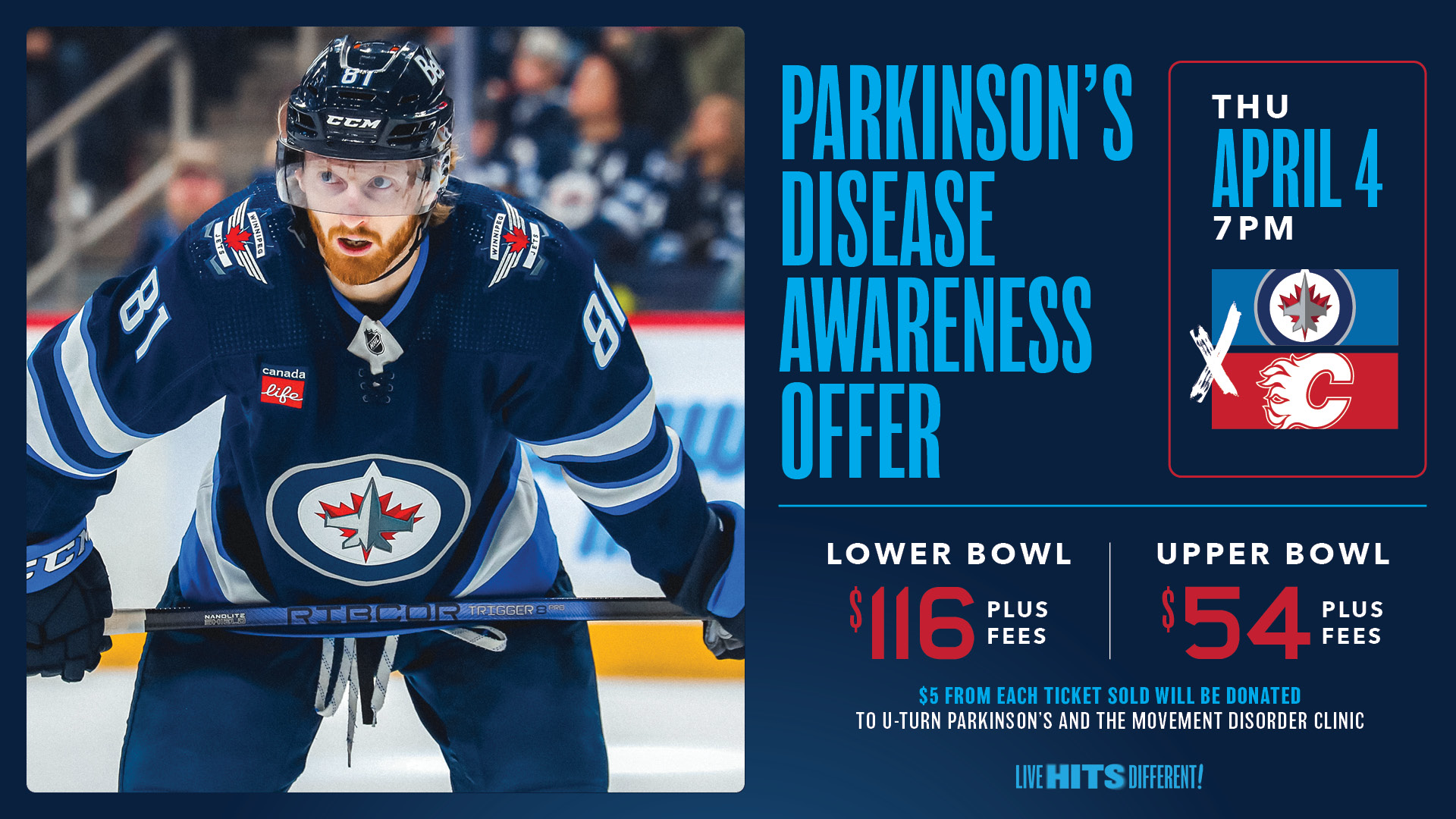

Winnipeg Jets Parkinson’s Disease Awareness Game!